It’s an overcast Presidents’ Day 2005. I’m on my way to the Packard building to work with my group on an EE108B lab assignment (something to do with pipelining in CPU design, or something). I’m running late for our 1 PM meeting, but I’m not in as much of a hurry as I probably should be.

As I pass by the Varian building, having nearly arrived at my destination, two little girls approach me on their bikes. The older one has brown hair and is dressed in pink from head to toe (even her bike is pink). I’d guess this girl is about seven. The younger one, presumably her sister, is still on training wheels, her blonde hair twirling out from under her slightly askew helmet. She looks maybe four.

I stop walking. The little sister looks through me, gasping, with her brilliant, electric blue eyes. Her alabaster face is stained with fresh tears.

“Excuse me! Excuse me!” says the big sister.

“Hi, is everything okay?” I try to appear nonthreatening, suddenly self-conscious about the goatee I would shave off a month or two later. The girl nevertheless speaks with the unflinching confidence of someone who doesn’t yet understand how dangerous the world can be.

“Do you know where the Peet’s Coffee is? Our mom works there, and we were biking outside, and we got lost.”

I pause. We’re far enough west on campus that I’m not 100% sure where they might have come from. “There’s two different Peet’s Coffees here. Do you know which one your mom works at?”

“No,” says Big Sis. The four-year-old whimpers.

“Okay, well, do you know your mom’s phone number?”

“No, but I know my dad’s.”

“Great! If you can tell me his number, I’ll call him, and we’ll figure out where you need to go. Does that sound okay?”

“Yeah!” She tells me his number, and I dial it.

“Okay, what are your names?”

“My name’s Elizabeth, and this is my sister Gracie.”

“And what’s your dad’s name?”

“Mark.”

I hit “Send” on my phone and listen to it ring. I’m not sure what I’m going to do if he doesn’t pick up, besides just try both Peet’s Coffees. Someone finally answers.

“Hello, Mark speaking.” He must be working today too.

“Hi Mark, my name is Prabhu — I’m a student at Stanford University, and I’m here with your daughters, Elizabeth and Gracie, who, I guess, got lost while they were playing outside?”

“Oh, no!” Mark exclaims, though he doesn’t sound as terrified as I expected. “Are they all right?”

“Yeah, they’re fine! Elizabeth mentioned that their mom works at Peet’s Coffee, but there’s two on campus, and I wasn’t sure which one, so I wasn’t sure where to take them. Do you know which Peet’s it is?”

“It’s the one at Tresidder.” Mark says Tresidder like he knows the place exists but hasn’t actually been there himself.

“Okay, great. I’d be happy to take them there, if that’s okay with you.”

“Yes, absolutely, that’d be wonderful.”

“And maybe you could give their mom a call?” I’m not sure why this, of all things, is on my mind, but I carefully avoid the phrase, “your wife,” for fear that the girls’ parents could be divorced. “Just to let her know that we’re on our way, and we should be there in maybe ten or fifteen minutes.”

“I’ll do that right now.”

“Okay, thanks. We’ll head over now, then.”

“Thank you so much for your help.”

I hang up, wondering how the girls even got this far from Tresidder in the first place. That’s a pretty long trek to make without realizing something is wrong.

“Okay, girls, I’m going to take you back to your mom now, okay?”

Elizabeth smiles and nods. Gracie, still sniffling, wipes her eyes, nods, and mumbles, “okay.”

I try calling Akshay to let him know I’ll be even later to our lab meeting than expected, but then I remember that none of us can get any reception in that stupid building anyway. We start walking.

As we pass by the Quad along Escondido Mall, Elizabeth walks her bike, and we make pleasant conversation. I still can’t understand how she is so comfortable with me. Gracie, meanwhile, pedals ahead, alternately cautious and speedy. She calls back to us, “Lizzie, I think I see it!” She, of course, sees nothing.

“Gracie, why don’t you walk your bike so you don’t get too far ahead of us?” I ask, fully aware that Gracie will ignore me as a matter of course. I understand now how these girls got lost. One of the scary consequences of children’s storied emotional resilience is that they don’t really learn from the bad things that happen to them. Gracie probably biked out ahead of her sister, excited to explore the world, and Lizzie had no choice but to follow; pretty soon, they were nowhere near where they started. Yet Gracie seems to have forgotten this recent trauma entirely; even the slightest nudge in the right direction from me has given her the misplaced confidence to explore again, striking out on her own with abandon.

“That girl is so crazy,” observes Lizzie, grinning and circling her left index finger next to her temple. I readily agree.

We round the corner at the Clock Tower, and the bookstore is in sight. I quicken my pace a little to try and keep up with Gracie, who is biking even farther ahead now that her surroundings look more familiar. Pretty soon, their mom, who has been standing outside in her Peet’s polo, waiting anxiously for her daughters to appear, sees Gracie and starts walking toward us.

It takes Lizzie and me a minute to catch up after Gracie and Mom reunite. The woman hugs her daughters, kneeling, and then looks up at me. She stands and takes my two hands in hers.

“Thank you so much for bringing my girls back.” Mom, a woman in her thirties, looks at me with a mixture of fatigue and relief.

“It was no problem at all.”

“I work at the Peet’s over there.” She points. “Can I buy you lunch or something?”

I look at my watch. “Well, actually, I’m running pretty late for a meeting, so I should probably get going.”

“Oh, okay,” she says, a bit disappointed. “Well, maybe you could stop by later for a cup of coffee.”

“Sure,” I reply. (I regret now that I never went back for that coffee; it’s a missed opportunity to have made a new friend.)

Mom looks me in the eye. “Do you have kids?”

“Not yet, no,” I reply, amused that this even seems possible.

“Well, you will someday. And the universe works in mysterious ways, but one thing I do know is, what goes around comes around.” I nod. “One day, they’ll need help like my girls did today, and God will send someone to protect them.”

I don’t know what to say. This is a lofty sentiment indeed. “Thanks, I appreciate that.”

I try to say bye to the girls, but Gracie is too busy clinging to her mother to pay any attention, and Lizzie seems to have acquired a new shyness in her mom’s presence. I bid Mom farewell and begin the long walk back to Packard.

* * *

There are a lot of things to be thankful for in this story. I’m thankful that Lizzie and Gracie happened to run into me, instead of someone that might not have helped them, or worse, might have hurt them. I’m thankful that, despite whatever coaching they might have received to be wary of strangers, the girls somehow decided that they could trust me. I’m thankful that Elizabeth was such a smart little girl: smart enough to ask for the Peet’s Coffee, smart enough to know her dad’s phone number by heart.

Most of all, I’m thankful that Gracie had Lizzie looking out for her. Without Elizabeth’s attentiveness, her instinct to follow her sister no matter where she went, this story could have turned out very differently. The charity of strangers comes and goes, but the love and care of a sister lasts forever.

Happy Thanksgiving.

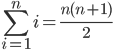

anyway; and many mathematically inclined adults know without thinking that the answer to the particular problem Jamie’s Dad posed is 5050. It may be true that achievement is at least partially a function of context, but it seems disingenuous to regard happening to know a formula that others don’t as anything other than, well, happening. (Yes, it is, in principle, possible for a

anyway; and many mathematically inclined adults know without thinking that the answer to the particular problem Jamie’s Dad posed is 5050. It may be true that achievement is at least partially a function of context, but it seems disingenuous to regard happening to know a formula that others don’t as anything other than, well, happening. (Yes, it is, in principle, possible for a