Not Exactly Carl Friedrich

Schoolchildren, like everyone, have love-hate relationships with a lot of things. They love lunchtime but hate what their mom packed them for lunch. They love recess but hate the stress of waiting to get picked in kickball. They love winter break but hate the last weekend before school starts up again.

One of the many classroom traditions with which I personally had a love-hate relationship was Teach-In. A quick search demonstrated to me that this word apparently means something entirely different in Orange County, FL, than in the rest of the world, so I should probably explain.

In my experience, Teach-In was a day when you’d have a guest speaker or two who’d tell you about what they do for a living. The idea was that exposure to successful professionals would get us thinking about our future career aspirations and would also help us understand how hard work now might pay off later. Often, the speaker was a classmate’s mom or dad, though it was sometimes just a volunteer community member. The reason I (and probably many others) had a love-hate relationship with Teach-In was that I loved getting out of yet another tedious lesson, but the guest speaker’s presentation was usually far more tedious than class would have been, and I hated that.

My most memorable Teach-In was in seventh grade, in Mr. Michalak’s advanced math class. The speaker was Jamie’s dad, and he was a computer programmer (I don’t remember where, but probably at some defense contractor). Jamie’s Dad (I don’t remember her last name, so this is about all I can call him) was a balding, brown-haired man with a mustache and a modest paunch that pressed against the patterned polo shirt tucked into his faded blue jeans. He was jovial and approachable, and he had a message for us that day.

The message began like this:

“So, who’s the smartest kid in the class?”

Each pair of eyes that flashed to me was like a missile designed by the company Jamie’s Dad probably worked for, carrying a warhead of awkwardness and embarrassment. Several classmates pointed unambiguously. I looked down at my desk, and then up at him.

“All right, I guess it’s you!” Jamie’s Dad smiled. I shifted in my seat. “What’s your name?”

“Uh…Prabhu.” I would be much older before I would finally learn to introduce myself without pausing apprehensively as though I were trying to remember my own name. (Somehow, in my entire youth, I only got called out on this once; it was by, of all people, a birthday party host at Discovery Zone, whose voice, whether real or affected, sounded exactly like Wakko Warner’s as he guffawed, “is your name so hard that you actually have to think about it?”)

“Prabhu?” Jamie’s Dad repeated.

“Yeah.”

“Okay, Prabhu. What I’d like you to do is get out a pencil and a piece of paper and add up all the numbers from 1 to 100. And while you’re doing that, I’m going to write a computer program that does the same thing. And let’s see who finishes first, okay?”

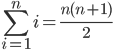

“…okay,” I mumbled in response. Meanwhile, my eleven-year-old mind raced. I knew how to do this in a way that had nothing to do with adding up numbers one after the other, which was obviously a dead end. There was a formula. My dad had shown it to me. I just had to remember it.

“Okay, go!” Jamie’s Dad’s fingers moved to his laptop computer, which was connected to a fancy little projector that made his screen visible to the entire class. (Such things were far from commonplace in 1996-97.) I’m not sure, but I think he might’ve been using Visual Basic.

As he started to type, I stared blankly at the piece of notebook paper sitting on my desk, its wide-ruled taunts daring me to fail. I couldn’t remember the damn formula. I picked up my pencil hesitantly, my neck burning red as I tried to forget that everyone in the class was looking at me.

It’s n times…something. n times…what would make sense here? n times…what was it that Dad showed me? We did this, like, just a few months ago. n times…something over 2. How could I forget? n times…(n-1)? What the hell’s wrong with me? Over 2?

I wrote this down. My neighbor leaned toward me, peering at my paper, presumably trying to understand what on earth I was doing, because I sure as hell wasn’t doing any addition. Okay, I guess I should go with this. Well, 100 times (100-1) over 2, uh, 100 times 99, over 2, uh… It’s very hard to remember in retrospect why I found this calculation even remotely difficult — never mind the fact that the formula behind it was wrong — but about all I can say is that I only had about sixty seconds for this entire train of thought, and I was hand-shakingly, mouth-dryingly, eardrum-poundingly nervous.

“Okay, done!” Jamie’s Dad exclaimed. I hadn’t finished calculating anything. I don’t remember ever actually looking at the screen, but I assume that whatever he wrote was functionally equivalent to

int n=0; for(int i=1; i<=100; i++) n += i; print(n);

“How far did you get?” he asked.

I stared at the tile floor. “I, um, I, well, I didn’t actually start adding, ’cause I, uh, I was, uh, trying to remember the algebraic formula…” I trailed off, sinking down in my chair, desperate to disappear into oblivion. I could have sworn I heard a collective sigh of disappointment from the rest of the class, who I imagine were hoping to see exactly how high this particular Icarus could fly.

Jamie’s Dad’s face donned a brief look of confusion, but he nevertheless rescued his demonstration with aplomb. “Oh, okay, well, I think the guy in the last class got to about 14 or so. And this is what make computers really powerful: they allow us to do things much faster than we could do with our own brains…”

And the moment passed. I honestly don’t remember a word of the rest of the lecture, but its first three minutes have endured in my memory.

One reason this failure sticks with me is how close I was to succeeding. More important, though, is how compelling success would have been. Stanford professor of innovation and entrepreneurship Tina Seelig has a saying: “Never miss an opportunity to be fabulous.” I’ve missed quite a few opportunities to be fabulous in my life, for reasons ranging from not even showing up to, well, not actually being fabulous. But in terms of the sheer gap between what I could have demonstrated in that moment (that I was faster than a goddamn computer) and what I actually did (that I couldn’t perform under pressure), it’s hard to top that day in Mr. Michalak’s class. It’s a very rare thing in life to have the chance to do something so completely beyond the expectations of your peers, and to come so close to doing it. In my own adolescent universe, whose governing truths were Kepler’s Laws of Solitary Narcissism and the Grand Unified Theory of Self-Absorption, I’d missed not just the opportunity to be fabulous, but the opportunity to be legendary.

Of course, the truth is that nobody in that room gave a damn that I didn’t get the answer, nor would they have really given a damn had I gotten it immediately. I’m fairly certain that not a single one of my classmates (few of whom I’m still in touch with) remembers this incident; neither, I can only assume, does Jamie’s Dad. More to the point, the fact that my dad had randomly taught me this formula one day actually says nothing about my being “fabulous” at all. It only says that my dad is. Everyone who’s taken any math beyond Algebra I has probably seen that  anyway; and many mathematically inclined adults know without thinking that the answer to the particular problem Jamie’s Dad posed is 5050. It may be true that achievement is at least partially a function of context, but it seems disingenuous to regard happening to know a formula that others don’t as anything other than, well, happening. (Yes, it is, in principle, possible for a smart person to reason out this formula without having learnt it formally, but I was very, very far from that.)

anyway; and many mathematically inclined adults know without thinking that the answer to the particular problem Jamie’s Dad posed is 5050. It may be true that achievement is at least partially a function of context, but it seems disingenuous to regard happening to know a formula that others don’t as anything other than, well, happening. (Yes, it is, in principle, possible for a smart person to reason out this formula without having learnt it formally, but I was very, very far from that.)

Still, I can’t help but wonder: what if I’d come up with the answer? Certainly, some people would have been impressed. And Jamie’s Dad probably would’ve been thrown for a bit of a loop, as I would’ve sent his carefully choreographed presentation off the rails. But how fabulous could fabulous have really been? Would I have been the talk of the school? Would I have gotten a special award of some kind? Invitations to advanced math tutoring at the local university? Would tales of my ingenious exploits have swept across the land like the stories of Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed, making me a veritable folk hero for nerds everywhere?

Hah. It’s fun to daydream about, but ultimately, I think it’s fairly clear that the only thing in my life that would’ve been different in any way would be this blog post. And I’m pretty sure this post is a far more interesting read than it would’ve been had I succeeded, so I suppose all’s well that end’s well.